Grief as an Excuse

Words by Monica Prince

Theme: Uncertainty

Nominated by Jessica McWhirt

I don’t know if grief is a good excuse for sterilization.

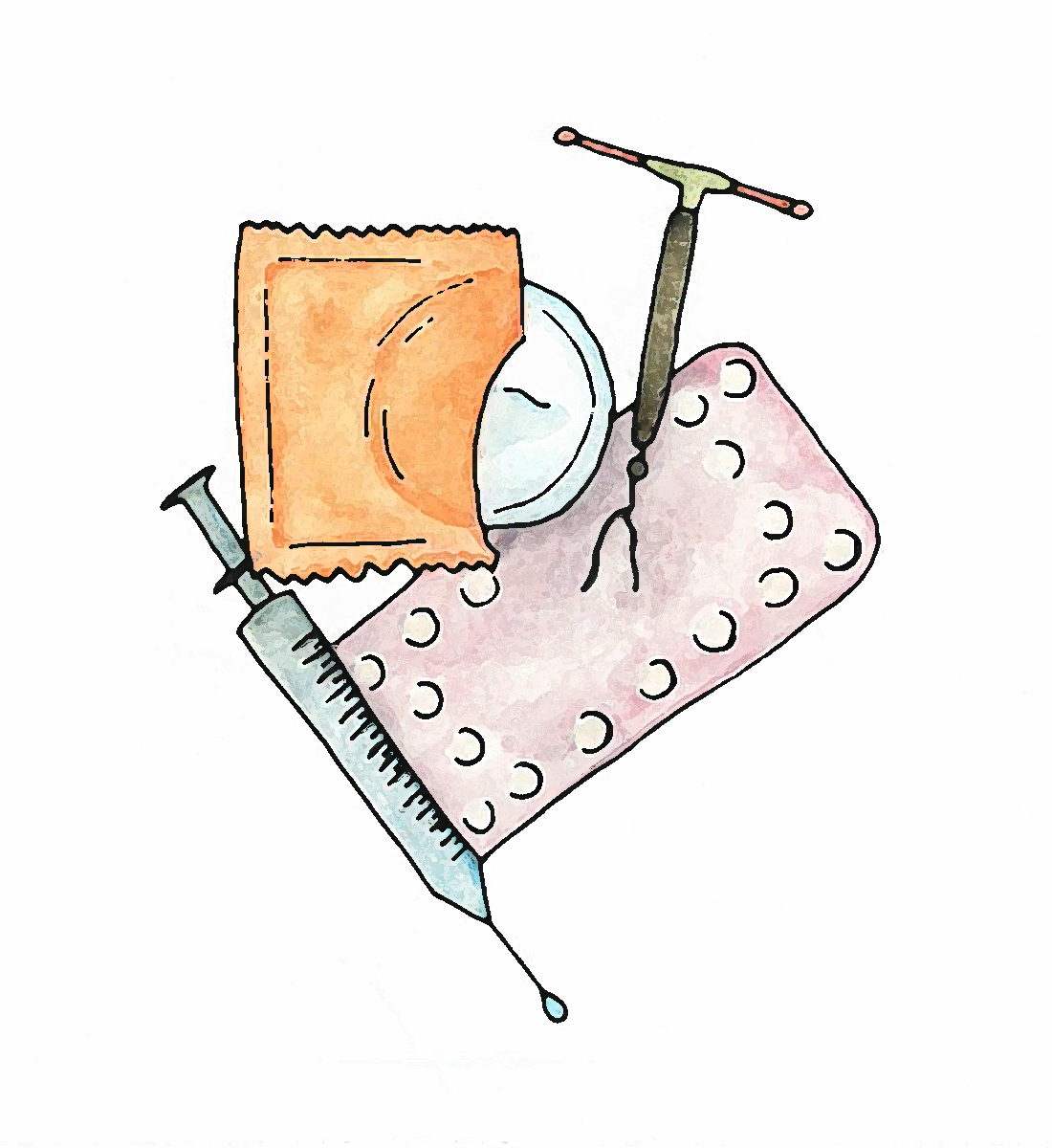

As of today, I have five essays, forty-two poems, and six thousand handwritten pages about my relationship with sex, pregnancy, and child rearing. When I think about uncertainty, I do not think about when the pandemic will end (eventually), if I will catch the virus (only took nine months), or if God is real. I think about loss. I think about grief. I think about survival. On the phone a few days after I received my IUD, my mother tells me she always suspected she had had a miscarriage but could never prove it. I’ve kept a journal since April 10, 2001. I was ten years old, going on eleven, and I decided I didn’t want to keep a diary—sounded too girly and therefore not serious, goddamn gender roles—so I created a journal. Originally, I wrote every single day. For days I missed, I’d recap what happened. In detail. That first entry, I lamented over Aaron Ramsey not liking me back (or was it Shane White?). All I wanted was to be desired. Not even loved or accepted or cherished—desired. Romantically. Sexually. Exclusively. I’m not ten years old anymore. I’m thirty. My journaling habits have changed, of course. But one thing that has never changed in the last twenty years is my desire to be desired. Not once. In my journal from my spring term of college (March-June 2009), I talk about an Arab man I met in the cafe who looks like Johnny Depp from Secret Window. I’m fascinated by him because he’s a creative writing major—like I hope to become soon—and he spends an early dinner with me and some other random people from my beginning fiction class talking about books. He has black glasses with a simple frame—my mother would call them a perfect fit for his face with her optometrist's eye—and long wavy brown hair. He makes piercing eye contact and has a nervous laugh that infects everyone at the table. When he leaves before the rest of us, he has a book in one hand and his saxophone in the other. I’m so wet my pants leave a print on the seat. What do I know for sure? When I fell in love with a man who understood polyamory, emotional distress, and what it means to be Black in America, I realized desire isn’t the same as sustenance. I refer to my first year of college in my journal as the year I tried to kill myself. The details aren’t too fun, but the proof is in my body count. I wanted to simply not exist. My guilt over breaking my parents’ hearts if I killed myself trumped my passive suicidal ideation, but it didn’t stop me from promiscuous unprotected sex with any man who would consent, drinking every weekend with people who didn’t care about me, or skipping meals for days on end. Adam, the writer with the saxophone, knew none of this. Here’s the short version: We had sex, twice, without a condom. He was worried. I told him not to worry. He didn’t know what that meant. I didn’t care. I took Plan B, as I’d done after every rape in the last year, and I continued my flirtation with Adam. My period was late. And then it came. I bled for about forty-two days—sometimes through my tampon, panties, and jeans, sometimes not for hours, convincing me I’d stopped. Adam panicked. I panicked. I scheduled an appointment with the family planning clinic down the street from our college for the end of May. For years, I never questioned why I wanted to get married and have kids. It just seemed like the thing to do—and it was supposed to make me happy. Though I was presented with evidence to the contrary on TV and in my own divorced parents, I just assumed my desire for someone else to desire me had to manifest in these experiences. If someone gave me what I so desperately wanted, the next step was children. When I come down with COVID-19, it’s my partner’s birthday. He spends the day taking care of me. I managed to elude him for twenty minutes to wrap an obscene amount of birthday presents in the last of the wrapping paper I have leftover from last year, and I nearly pass out alone on the floor from exhaustion. “You didn’t have to do this, why did you do this?” Rob asks when he returns to the bedroom to a pile of badly wrapped gifts next to the bed. He sounds annoyed but he’s smiling. “Open your presents!” I exclaim, but my headache reminds me to calm down. I’m trying to apologize for getting this trash virus on his milestone birthday, but he says all he wants is to spend time with me. Until, of course, he discovers that I got him NBA 2K21. I pass out on the couch while he plays, wrapped in a blanket, rising to consciousness occasionally when he kisses my forehead each time he returns to the room.

I’ve had six years to process this loss, and I always circle back to what right I have to grieve it at all. Do I get to miss a bundle of cells I didn’t know could have been my child? Do I get to name them?

I believe my mother didn’t want to be a mother, but I will never confront her with this. I do not know if I want to confirm it. I’m uncertain of what it will do to me, what it will do to our relationship. I’m afraid it will estrange us. I’m also afraid it will make us closer. At the family planning clinic, the nurse practitioner asks why I’m here. I tell her about the blood and how I’m scared that something’s wrong. She says she can’t examine me while I’m bleeding, so she prescribes me birth control pills and asks me to come back in a week. The pills work. I stop bleeding. At my follow-up, she recognizes my recklessness before I even disclose it. She gently tells me to be more careful in the future, writes me a prescription for a year, and dumps fifty condoms in the paper bag next to the month-worth of pills. I stay on birth control until I graduate college as a precautionary measure against future menstrual irregularities (at least, that’s what it says in my chart). It’s the only act of self-preservation I commit that year. Meanwhile, Adam and I stop having sex, but we stay friends for the rest of our lives. In a bar in New York on the fourth of July exactly ten years later, we drink gin and tonics and confirm our memories. I refer to our relationship as a trauma bond. “Well, yeah,” Adam agrees, adjusting his glasses. We’re older now, employed with five degrees between us, and I still feel hopelessly in love with him. I think about how that love has changed—less about sex and conquering, more about mutual respect and the safety of someone who has seen you in your worst moments. “But that’s not the reason we’re still friends now. Usually trauma bonds are toxic, aren’t they?” “True.” He’s engaged, getting married in six weeks. I’m single and practicing polyamory. “And besides—it was just some unprotected sex and a bad reaction to emergency contraception. It’s not like we actually had a kid together.” I don’t want children. I vocalize this desire in January of 2020 during a conversation about health with Rob. When I say it, I surprise myself with relief at telling the truth. I down my gin and tonic. “Actually—I don’t know if that’s true.” Adam tilts his head. “What do you mean? You mean, it was a—?” It’s in the Woman’s Care Center behind Taco Bell in Milledgeville, GA that I learn about my miscarriage four years prior. It’s May of 2013. I’m renewing my birth control prescription with a new provider. Dr. Jessica has the perfect Southern accent. Somehow, this calms me when she asks me questions about my medical and sexual history. She doesn’t blink when I tell her how many sexual partners I’ve had, and she doesn’t ask me if I need a full STD screening; she just takes my blood and urine and runs the tests. When she asks why I started and stopped taking birth control, I tell her the story of Adam, noting the six weeks of nonstop menstruation and the use of birth control to regulate my uterus’ panic attack. After a beat, Dr. Jessica clears her throat as she makes a note in my file. “I don’t know how to tell you this, Miss Prince,” she says, her accent elongating the single syllable of my name into two. “But I think you had a miscarriage.” The room doesn’t stay silent as the nurse practitioner peruses my paperwork in the corner, the shuffling of papers and buzz of fluorescent lights reminding me I’m still alive. “What?” “All that bleeding. It probably wasn’t caused by the emergency contraception. In all honesty, you may have taken it too late and it may have only held the lining in your uterus for a few weeks longer than usual. But for that lining to shed for over a month—you had a miscarriage.” I stare at her and blink once. “The baby wasn’t even a baby yet, though,” Dr. Jessica quickly adds. “But I’ll note it in your file just so we can watch out for it in the future.” I leave with my prescription, fill it at the Kroger pharmacy, and take the long way back to my apartment. I pop my pill and chase it with a glass of wine. I don’t tell anyone. I don’t know what to say. Adam asks if I’m okay. “Now? Absolutely.” I’ve had seven years to process this loss, and I always circle back to what right I have to grieve it at all. Do I get to miss a bundle of cells I didn’t know could have been my child? Do I get to name them? “Are you okay?” I ask. Our new drinks arrive in the brief silence. “I mean, I guess so.” I shift in my seat at the pang of guilt that shoots through my lower abdomen. I should have told him sooner. Suddenly he smiles and lifts his glass. “At least we still have each other. Trauma bonded or not.” I clink my glass against his. In my choreopoem How to Exterminate the Black Woman, there’s a poem called “Loss as a Canyon.” After Silence tries to commit suicide on stage and fails, Loss rushes to her side, disarms her, and tries to comfort her while Silence sobs uncontrollably. A dancer enters silently, pockets the revolver, and moves to take Silence off stage. But Silence revolts—she kicks, she cries out, and she struggles against the dancer’s efforts. The dancer ultimately succeeds and starts to drag Silence off stage as Loss looks on in horror and defeat. But before the dancer can get Silence out of sight, she screams, “What if they kill me first?! What will my mama do with my body?” The moment holds for about ten seconds before Loss finally turns to the audience and recites her poem. “When they call out crater, canyon, valley—they mean me,” she intones. “At eleven, I visited the Grand Canyon. I didn’t know I was reading my own palm. At eighteen, I miscarried what I imagined to be a son. Ever since, I’ve only wanted daughters.” It’s not the first poem I’ve written about this time in my life. It’s not the first one where I’ve named the child. But it’s the first where I wonder the point of this practice. “What good is memory if its only service is to suffocate you?” Loss asks. I don’t know. I don’t know. Rob doesn’t know if he wants to sire children. He claims he might want a vasectomy one day. I want him to make this decision without me. But the problem with love, with the forever kind I’ve built with him, is no decision either of us makes ever again will be alone. I shouldn’t call this a problem. It’s what I’ve wanted my whole life. Of this I’m sure. After the pandemic goes into full swing in the U.S., the dreams I remember are nightmares surrounding pregnancy. When it’s finally safe enough to see my gynaecologist, masked up and distanced, I express my desire for sterilization. The only question he asks me is how old I am. There’s that relief again. My mother doesn’t want me to take such a permanent solution to my fear. She believes I’m impulsive right now because I’m afraid of my friends and family dying from COVID-19. She’s not wrong, but she’s also wrong. In a counselling session in which I rant about the poor care I received from the physician who inserted my IUD, my counsellor asks me why I get defensive whenever anyone questions me about my desire for sterilization. I go in verbal circles talking about societal expectations of women, about not wanting my life decided for me just because I’m a woman of a certain age. I outline the inappropriate surprise people express when they find out I don’t want children, how it turns to genuine anger when I talk about sterilization. “It’s like I’m offending them by not doing something that won’t impact their lives at all,” I spit. “Everyone talks about the joy of motherhood, but no one talks about how Black women are more likely to die from childbirth complications because their doctors don’t believe them to be reliable reporters of their own bodies. No one talks about how they almost let Serena Williams, the most powerful athlete in the world, die on the birthing table because they didn’t believe she knew something was wrong with her own body. No one talks about how hard it is to be a mom unless it’s under the guise of humor. The only people being honest about the constant worry for their children are the ones whose children have died, or worse, been killed.” I take a breath. There it is. “I will not survive my child being killed by police or racists or homophobes. I will not survive my child becoming a hashtag on Twitter with the words ‘Justice For’ preceding their name. I can barely manage the vicarious grief I feel every time someone who just looks like my brother or my sister or my cousin or my fucking life partner ends up killed because they were Black and breathing. These people want me to conceive and give birth to a target that I will put my whole life force into, that I will love more than anyone or anything else I’ve ever loved, and they want me to do that for what? So I can die from heartbreak if I have to bury them? No. No.” My counselor doesn’t interrupt me. She has this look on her face that says she believes me. I fold and unfold my hands and sigh. “I just want the choice to avoid suffering for once in my life.” I don’t know if grief is a good excuse for sterilization. I turned thirty during the pandemic. In my journal from ten years ago, a list of things I hoped to accomplish before this milestone birthday reflects not nearly enough of what I believe now, what I know now to be true. I’m not married, have no kids, no doctorate, and my student loans are out of control. But I’m so happy I could burst. Sure, I still suffer from depression and PTSD. I can’t run a mile without stopping. My natural hair isn’t totally doing what I want it to do. But I have three books. I’m teaching the best students in the country. I’m wildly in love. God am I happy. Joyful even. That feels like enough. It has to be. Let the unknown take its best shot.

Monica Prince teaches activist and performance writing at Susquehanna University in Pennsylvania. She is the author of How to Exterminate the Black Woman: A Choreopoem ([PANK], 2020), Instructions for Temporary Survival (Red Mountain Press, 2019), and Letters from the Other Woman (Grey Book Press, 2018). She is the managing editor of the Santa Fe Writers Project Quarterly, and the co-author of the suffrage play, Pageant of Agitating Women, with Anna Andes. Her work appears or is forthcoming in The Texas Review, The Rumpus, MadCap Review, American Poetry Journal, and elsewhere. Find her at monicaprince.com

Monica Prince nominates Penny Dearmin

Nominate.

The purpose of Artemis is to increase the range and diversity of stories shared and written by women. Therefore, Artemis has one rule, nominate! To write for us you must either nominate someone or have been nominated, so if know you a woman who has a great story to share, fill in the details below!